In these works, Pierre grapples with the complexity of growing up as a black African male in Australia. His interior life is prised open as he attempts to find himself within the coalescing views of Christianity, Kongolese spirituality, tribal ritual and voodoo.

—Leigh Robb

Exhibition Dates: 17 June – 17 July 2021

Pierre Mukeba arrived with a force on the Australian art scene with his first solo show held in early 2017 at Greenaway Art Gallery when he was only twenty-two years old. Titled Trauma, the exhibition featured fourteen large-scale full-length portraits of black men and women, small boys and a mother and child. The figures were rendered in fine pen and ink on plain calico sheets, their bodies clothed in bright African fabric. These images were sourced from the news or were based on memories from Pierre’s childhood, growing up during the civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo and then in refugee camps in Zambia and Zimbabwe. Pierre was eleven years old when his mother sought asylum in 2006 for herself, Pierre, and his sister in Adelaide.

In the past four years Pierre Mukeba has produced an astounding body of ink and textile works for which he has gained wide-spread recognition. They have featured in the 2017 Churchie National Emerging Art Prize (which he won); 2019 Ramsay Art Prize; 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art and the 2020 NGV Triennial. Pierre is the only African Australian artist to be included in Phaidon’s anthology, Vitamin D3: Today’s best in Contemporary Drawing.

Drawing is at the heart of Pierre Mukeba’s practice. The artist’s private working art journals and small accordion notebooks are filled with vivid and often violent scenes and figures to be worked up into his large-scale textile drawings. These drawings reveal his rigorous approach.

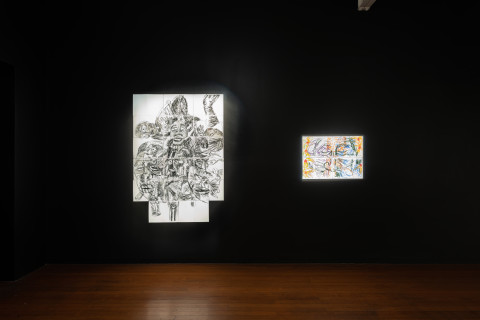

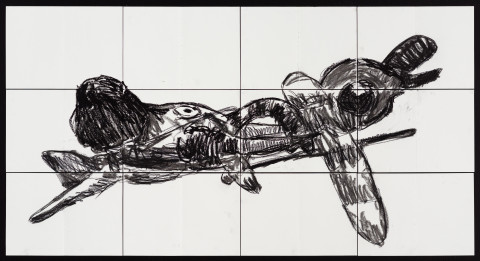

Black Emotion marks a decided shift in Pierre’s practice and subject matter. After an intense four years of art prizes, fairs, major national group exhibitions, and thwarted attempts to move to Europe in 2020, early this year Pierre moved back to live with his mother, younger sister and nephew in their Adelaide home. Black Emotion represents a selection from the outpouring of more than one hundred multi-panel charcoal drawings produced in the past six months - and his most personal series to date. Pierre says, ‘I was in an unknown space in my life and I wanted to experiment, be expressive and not have to overly manipulate the images’. For this body of work he turned to charcoal, an immediate and fugitive medium that could be channeled at speed to match the rapid expulsion of images. Even the material construction of these works on paper represents a process of opening up. Each drawing is comprised of multiple unfolded sheets of A3 paper. Charged with emotion, the pressure of the line and velocity of the mark distinguish these works as strikingly different from his deliberate works on fabric.

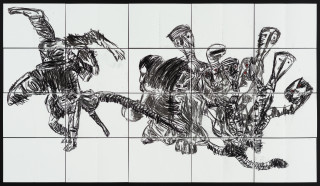

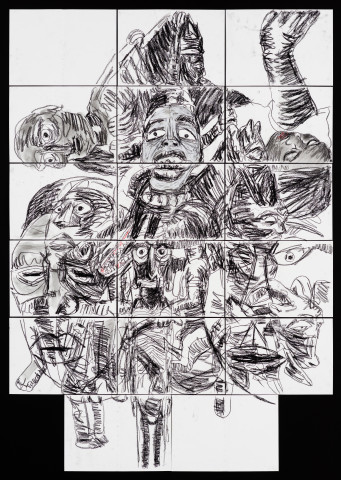

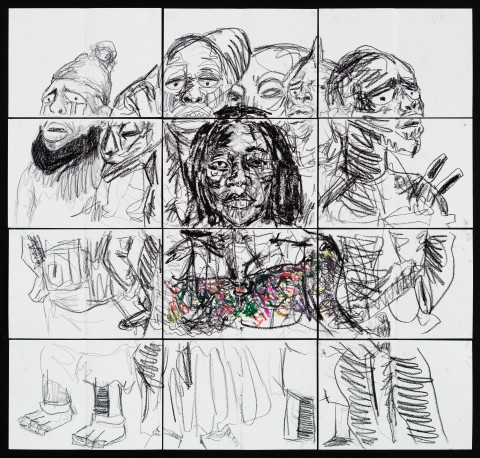

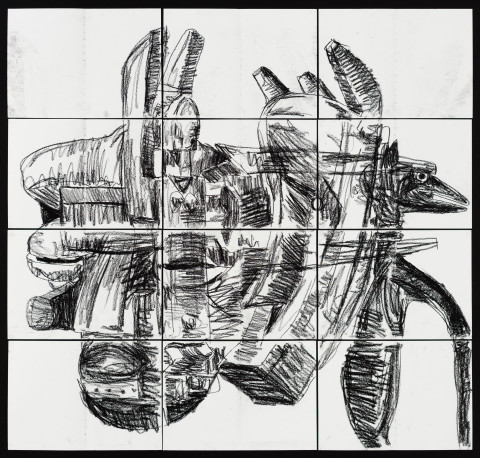

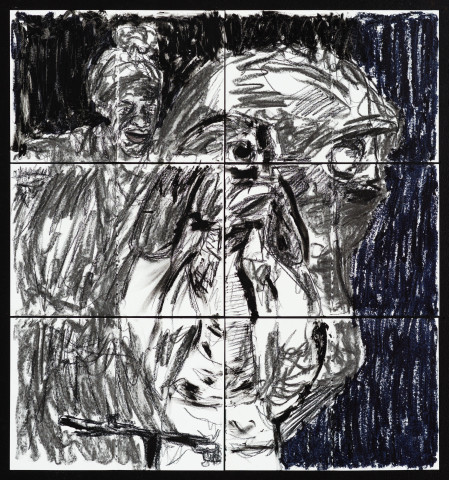

In these works, Pierre grapples with the complexity of growing up as a black African male in Australia. His interior life is prised open as he attempts to find himself within the coalescing views of Christianity, Kongolese spirituality, tribal ritual and voodoo. Westernised notions of individualism are in irreconcilable conflict with the responsibility to family and community. These overwhelming tensions are felt most keenly in (Reflection Of The Soul). At the centre of the image is a self-portrait of the artist holding a fish in his teeth. Surrounding and overshadowing him is a chorus of figures, faces and eyes, referencing carved wood Kongo nkisi statues, and masks. In the upper left the image of his mother hovers. In this work, Pierre has spoken about accessing different states and dark energies, concepts of deliverance and wrestling with self-destructive demons. He said these works represent ‘a double release – when I can see it and then draw it, I can let it go’.

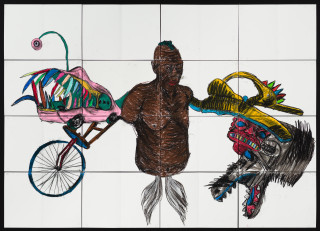

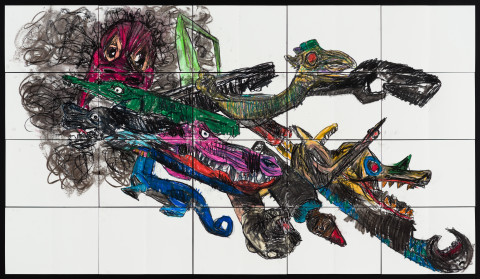

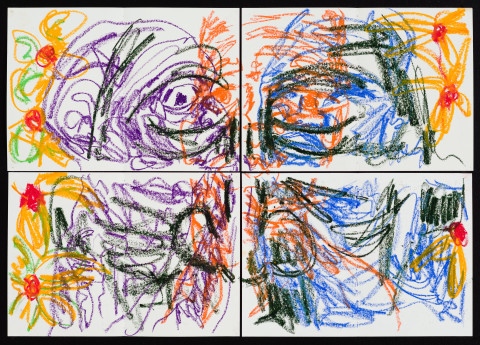

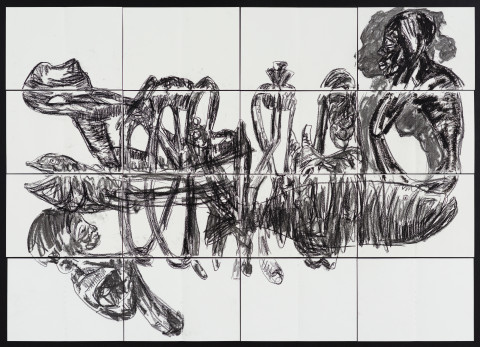

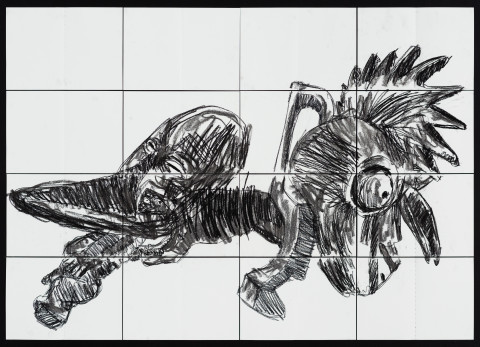

Many of these drawings honour family and bring them into his artistic world. His nine-year-old nephew and his love of video gaming is captured in the coloured pastel and charcoal (Baby Folklored Dragon). Over two meters long, snapping jaws of dragons and crocodiles project diagonally across the pages, like a creature with many-forked tongues. In (Intensely Masked Dolphin) Pierre represents his sister camouflaged beneath layers of dolphins, her legs barely visible underneath. Pierre is making a comment on his sister’s self-protective instincts. Like many of his works using coloured pastel, the mass of conjoined images appears to pivot on a fulcrum. At the centre of this work is a dog biting the horn of a dinosaur, the left a cascade of coloured dolphins, the right a purple elephant. There is often an extreme tension or balancing act being performed in both the composition and graphic weight of the imagery and the interplay of the heaviness of the charcoal and competing palette of the pastel.

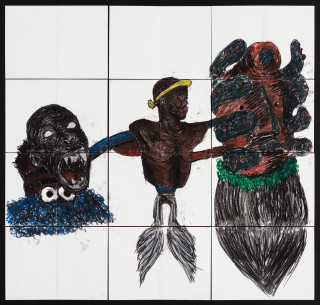

In Christine Kitenge Pierre pays tribute to his mother. He depicts her surrounded by six self-portraits of the artist. In this work, the artist captures the strength of his mother; a pastor, a single mother for twenty years who speaks five languages –Swahili, French, Lingala, Ciluba, and English – who navigated his family to safety and who continues to ‘hold his different selves together’. Another work dedicated to his mother is (SAMAKI), which means ‘fish’ in his mother tongue Swahili. It features the skeleton of a fish after eating a meal. Fish repeatedly appear as symbols of nourishment and are cooked almost daily by the artist’s mother.

Black Emotion includes Pierre’s first direct self-portraits. In Christine Kitenge, his self-portraits shift form between human and spirit. The figure on the left is wearing Western clothes, but has the feet of a wooden statue, whereas on the far right, the artist appears as a male nkisi power statue often used in rituals for healing, with nails protruding from his upper shoulder, whilst the figure in the background wears traditional chieftain garments. Central African wooden statues, of which the artist has his own collection, appear intertwined throughout the drawings, and some connect to his father’s Bantu tribe, the indigenous Kasai.

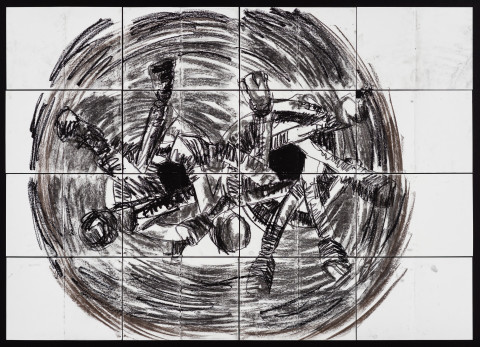

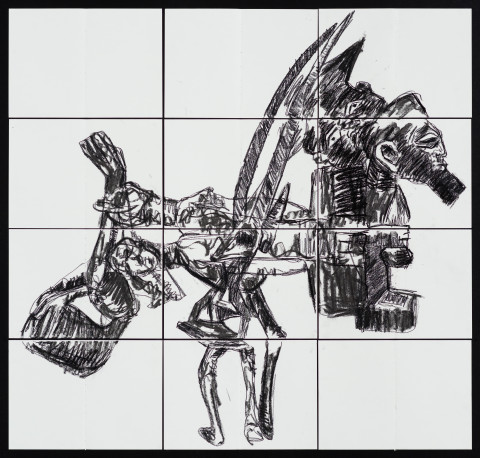

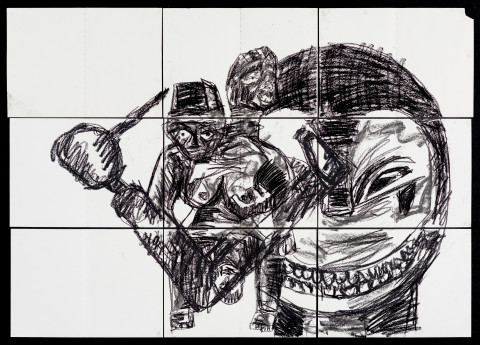

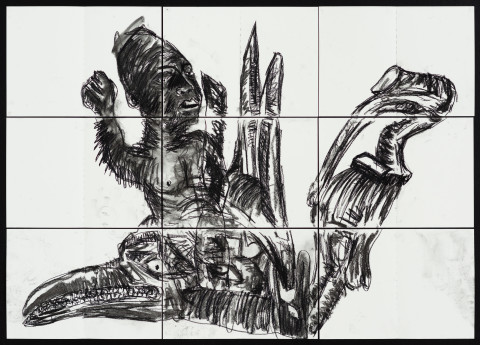

A recurring motif throughout these charcoal drawings is the fragmented, metamorphosing figure, the torso of a man being propelled by black wings, balancing two opposing forces, as seen in (Cognitive Dissonance), KINGA and (Hood Hyena). Pierre speaks about ‘the demons that I fight every day’, from balancing friends and family, to Christianity and Animism – bared teeth and gaping jaws threatening to bite at his wings and his precariously held equilibrium. Black Emotion reads as an artistic rite of passage – a cathartic coming of age that Pierre has defiantly and publicly shared.

— Leigh Robb