Annette Bezor's first solo exhibition at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery.

Exhibition Dates: 16 September – 4 October 1986

"The world of woman touches the world of men, moreover, at so many points that I to paint woman is to paint us all, from the cradle to the grave. It will be the

characteristic mark of the art of this century that it has approached contemporary life through woman. Woman really forms the transition between the painting of the past and the painting of the future"

Camille Lemonnier

These sentiments were written at a time when the painting of women had become the obsessive pre-occupation of late nineteenth century Symbolist art and literature, when for the male painter and poet alike the primary subject was the enchanting lure of the enternally feminine. "The image of woman was at the very

center of his aesthetic and moral principles as well as the crux of his deepest psychological motivations"

It is a fitting artistic politic for Annette Bezor, a late twentieth century "fin-de-siecle feminist" painter (strange bedfellows indeed) to turn her attentions to the female oriented aesthetics of the Symbolist period for an interpretation of a contemporary feminine allegory.

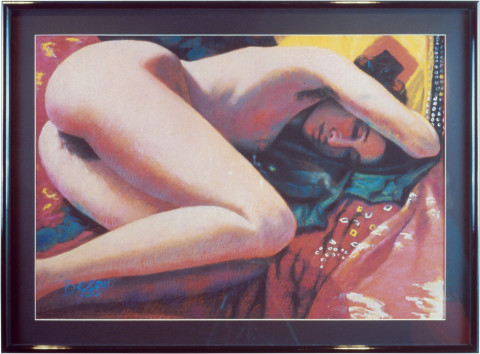

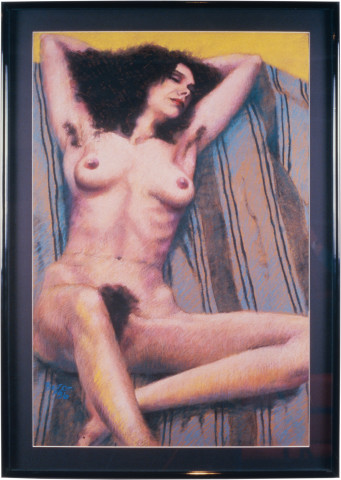

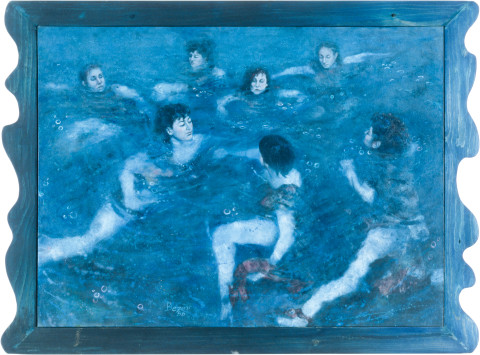

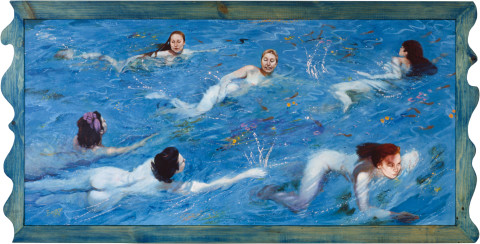

Her "Heads Above Water'' series of paintings reflects and refers to a lengthy western tradition of male artists who had painted the female nude as a bather swimmer. Such images of the female in art have always functioned as ambiguous symbols, primarily sensual and formally and hieratically sublimated into an

acceptable and relatively tasteful "ideal" of Beauty. This constitutes a noble and therefore philosophically significant subject for the traditionally voyeuristic male connoisseur-aesthete, who was hence considered the most informed and apt interpreter of the possible meaning of the "historical" female body in art.

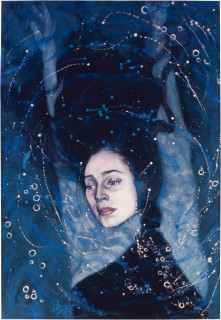

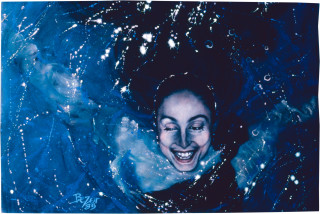

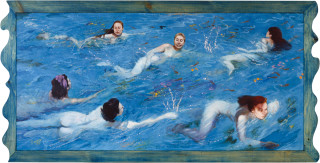

In the series of the four large paintings, Bezor has produced her most succinct and complete metaphoric work so far. The female figures (each is a portrait of

a friend, including her own self-portrait shown three times) undergo their journey of relationship and trial, essentially alone, placed by the artist in a substance that could not be more redolent with possible meaning as a narrative symbol for a drama pertaining to art, sexuality and the self.

In the first of the four paintings, seven women cluster in a central vortex, heads held above the water with difficulty; there is temerity and the mouths tightly shut. The water is dark, murky and foreboding, their skin is deadly pallor and the chilling blue suggests a cold temperature and eclipsed light. The only concession to 'life' is a self-conscious, feminine, rouge-painted cheek. In the second painting, action has been initiated, the vortex is broken and the women disperse, splashing, the faces are somewhat more relaxed. There is now revealed some evidence of the female sex but it is obscured by the ungainliness of the struggle to move. The faces seem both interested and yet distant, no gazes meet; the concentration required to stay afloat is critical. One figure appears to be sinking. In the third painting, the women are all submerged, there are no faces to register fear or hesitation, in the act of submerging there is a speed and corresponding direction for the swimmers. Light seems to emerge from within the painting, the cold anxiety of the previous two pictures is gone and there is now more evidence of female shape and natural sensuality. The figures seem to have gained mobility as their hair has come loose. In the final painting the ordeal of symbolic submergence has been, mostly survived. One figure is lost, missing, an inevitable casualty. Their faces and gazes now address each other, the isolation of the ordeal by water turns into a communal activity, drama and anxiety have been transformed into play while the artist, the figure in the lower right, does not appear convinced and makes ready to move on but is confined by the picture frame to her symbolic painterly ordeal.

What then are the implications for Bezor, the late twentieth century ''fin-de-siecle feminist painter, who has turned her attentions to the female oriented aesthetics of the Symbolist period? She, like other contemporary artists who acknowledge the 'post-modern' predicament and who see themselves as working within it, confronts the issues off'appropriation', originality and the author, the subject and the self and, finally, the satisfactory or otherwise acceptance of the art work as an aesthetic token or cypher within the various theoretical regulations that have emerged for the reading of visual practices. If Bezor is working from a strongly feminist perception, then the above concerns take on a different value within the machinations of a disputing 'avant-garde'.

Over and above Bezor's use of Symbolist subject, compositional references and their diverse methods of representation, there emerges a powerful, confronting, struggling and free female awareness, riding like a Botticelli Venus with her own outboard motor on an allegorical sea - traditionally the drowning substance of female identity. She has chosen to work within conceptually difficult confines, for the aesthetic movement, English and continental, meant manacles for women while it proved sexually and libidinally liberating for male artists. Bezor achieves a perverse switch on this situation while engaging in a dissembling practice which at a superficial level might bring down the indignant wrath of male and female artist, historian and critic alike.

In Bezor's work, female 'identity', 'awareness' is pushed literally up onto the surface and into being. Her concentration on the female face, its subtlety, its recording of each inflection of mood and thought is as the mirror to the woman; it is her constant as a material being.

The decisive element in this rococo fantasy of mirrors is that the mirroring activity in Bezor's work is not drawn across the face of a watching male and then onto his canvas; there is no male suggested, indicated or even invited into these pictures. The female is looking at herself for her own pleasure as a reflection of her own experience - she is her own voyeur and as such drains the act of the symbolist male's need for mystery and the overlaying of sex with religion. It is irrelevant that a thousand males might see these paintings, what is important is who they were done for. What a moral shook for those who have accepted the 'history of Arts' tenet that voyeurism was the exclusive domain of the all knowing and encompassing male eye. In the wresting of control of her image for herself, is the feminist challenge here. Is her self-gaze a threat to the male gaze? If there is male or female discomfort in the viewing of this exhibition then there should clearly be no confusing of it as a matter of taste or a squeamish fall back on to 'good' art versus 'bad' art. These things go and Bezor has probably hit the history of art in the softest and most vulnerable part of its belly ... the domination and control of art, and, through art, of woman. Break the one and you have broken the other. However, as in the late nineteenth century, the prospects of such a power struggle are dim, and, as with Bezor, the best we can do is keep our head above water.

As for her implication in the 'post-modernist' pastichists/parodists versus the old 'avant-gardism', Bezor's work happily gives that debate the coup de grace. Donald Kuspit in a recent article attacks what he sees as the singluar 'narcissism' of the 'new appropriators'. According to him, Bezor would fall into this category, considering her re-creation of Symbolism without its original (dubious) Idealist (the idealizing moralists of the subject in art as it is tied to style and form are gasping for air), Kuspit might apply to her brand of 'narcissism' the view that ''Like the consuming world, neo-art in general over-objectifies the 'original' art it appropriates - appropriation is inherently over-objectifation - thus destroying it''. What could be better for a feminist when appropriating the form and subject of the Symbolists? In 'destroying' it all that is destroyed is its fatal and 'fatalizing' use of woman. As for his view that today's artist copies old art in order to give it 'at least second hand authority', this again is undermined by Bezor. Her work represents no purified nostalgia, nor is it just a 'seductive set of signs'. The 'nostalgia' or as I prefer to call it, empathy, is for real women as they exist and have existed, mirror fetish and all, within the dominating matrices; the 'seductive' in her work is as sexual pleasure not as moral misdemeanour, as Kuspit (who seems more and more to display male Symbolist phobia) suggests the implications of seduction to be. Admittedly, in many instances I would agree with Kuspit when he attaches 'post-modernist' appropriations for "simply piling intellectual appropriations upon aesthetic appropriations anally mouthing what is fashionable to understand and fetishize, as if treating it as though it was created in a vacuum was a sign of truthfulness'', In Bezor's case the matter is quickly sorted and clarified when a feminist perspective is applied. Herein lies the unique political role of feminist appropriation within 'post-modernism'.

Perhaps one could take Lemonnier's statement ''Woman really forms the transition between the painting of the past and the painting of the future" a little further by saying that Woman, and especially the woman artist, cannot proceed into her own future unless she tampers with the painting of the past.

Excerpts from "Heads Above Water" by Elizabeth Gertsakis

London, June 1986

Entire essay available on request.