Ian North's third solo exhibition at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery.

Exhibition Dates: 29 July – 15 August 1992

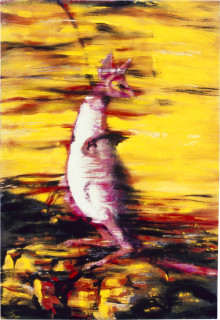

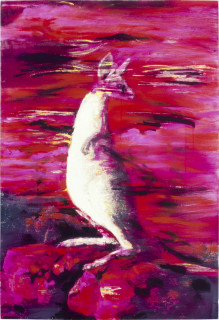

Altogether hybrid: these recent series of works with the titles Home & Away and Five Seasons in Magenta: Kongouro by Ian North play a game of visual and cultural dyslexia in an attempt to dislodge our preconceived notions of a projected and unified vision of place. In eerie yellows and off-register crimsons and magenta, and using the unlikely method of acrylic paint over black and white photographs, North has constructed both in content and form visions which over-ride the simple acceptance of colonial fusions.

Pushed together in the middle of the large Home & Away panels are the borrowed visions of imperial past and explorative future. Or read another way, the imperial homeland the colonised and hotly contested last frontier. On the right hand side of the works, the tip of the iceberg: an image culled from Antarctic photogapher Frank Hurley, whose expeditionary images are both product and symptom of a time in which imperialism, in melt-down, was attempting to cling to Cartesian claiming. On the left hand side images depicting the sleepy hollow of the English countryside from a book of pastoral photographs by J. Dixon-Scott; images of order, cultivation and mummification. Fused together in the middle, by means of an awkward smear of colour, here and there, these images of the foreign, unseen and majestic encountering the familiar, catalogued and ordinary, produce a discord.

The clue; if you need more, of these images, perhaps lies beneath the tip of the iceberg. Below what can be seen, what cannot be catalogued and turned into something other than itself. The invisible underside of the iceberg denies the imperial measure. Unfathomable, it works against the opportunity to transform fact into a convenient fictions. Equally it begs an imaginary accomplishment on the part of those who would still attempt to categorise and claim.

Issues now well documented and mused over in the past decade also surface in these strange vision collisions. It hardly needs saying that culture and nature and isues of exploration and catgorization are themselves metaphors for the psychoanalytic tip of the iceberg which has emerged thus far in debates about gender and difference. Perhaps unintentionally North has inherited these issues and unconsciously placed them here in a gothic tale of order and chaos, restrained and exuberant colour. In looking at these works I see issues of domesticity and passivity of the motherland: simultaneously I see the omnipresent state of motherhood as the pro-active shaper of foreign territories, and for me the intriguing question of exploration in the name of the mother (and one thinks here of the great queens who have driven avarice-based expeditions) strangely overworks the idea of man as conqueror.

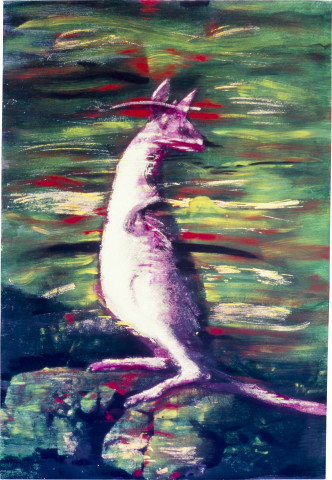

In this sense then the corollary to this is the forlorn image of the Kongouro, oddly wrong yet near anatomically correct; wounded, discoloured in a range of arbitrary colours. This rather brutal encounter with the imagined animal, poised somewhere between nobility and farce is the iceberg exposed in the minds of explorers. Inaccurate to the extent that it operates a form of forced extinction of the real, this image drawn from colonialism, quasi-science, and the perverse dyslexia of the 'European' araldited to the 'indigenous', the Kongouro is the melt-down factor in its magenta mix of tar and pigments of both our contemporary condition and the past that has shaped it.

North combines satire, humour and irony in these works, a sweetener perhaps to the seriousness of the bitter issues which surface in the content and veneer of these works. In this sense he reminds me of a Swiftian, and indeed the explorative aspects which are drawn upon, quite literaly here, suggest North's continued interest in the follies of so-called Enlightenment, which keep us perpetually in the dark and desensitized to what we really see.

Juliana Engberg

July 1992